#8 - The Monkees "Riu Chiu" (1967)

Click above to hear "Riu Chiu"

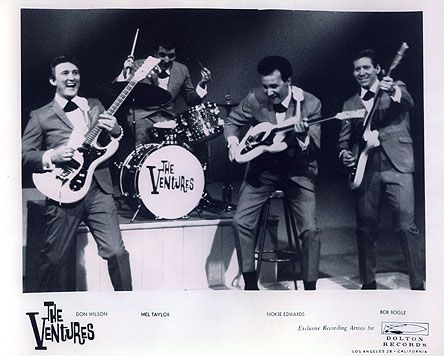

Enter The Monkees - Micky Dolenz, Davy Jones, Mike Nesmith, and Peter Tork with their Christmas musical offering from 1967.

This is my indulgence on this list, my attempt to shake it up a bit and feature not only an obscurity but a song which has stuck in my mind for years. I never get tired of watching and hearing it, and prior to seeing this I had never heard the song, and definitely did not associate it with any Christmas music program I had experienced. So it became my own tradition, one which I listen to often every December. And if I just want to hear it, I’ll play it any time of the year.

I’ll admit as a disclaimer in advance, I’m a heavily biased fan of The Monkees. Their music makes me happy, their music was a big influence on me as a musician, and I try to share and promote their music with as many people as possible, especially those who know The Monkees more by reputation than the actual quality of the music they released. Their television show was groundbreaking for its time both technically and thematically, their film “Head” is one of the most unique, bizarre, and most enjoyable films ever made, and overall the legacy will continue as more people reevaluate and revisit their work and base opinions on what they hear and see for themselves.

How do I comment on this, then, without that bias coloring every comment? That would be impossible. Again, consider this entry my personal indulgence in the series.

When considering this performance, I try to put myself back in time, and into the mindset of someone settling in watching the family television set December 25, 1967 as this episode aired on NBC, the fifteenth episode of the second season and the forty seventh episode of the series overall. Called “The Christmas Show”, it was a sweet holiday episode about a kid who lost the Christmas spirit, as played by Butch “Eddie Munster” Patrick. The episode had no music until the final minutes, and the music was not woven into the show in the form of a video interlude which was the show‘s trademark. Imagine the shock and surprise when in those closing minutes the camera cuts to the band seated around a microphone, with Micky Dolenz holding a lit candle and Peter Tork holding incense.

Wait a minute…some viewers and fans must have thought…what is this? Where is the madcap romp, where is the music video featuring quick-cut editing and free-form camera work which we’re used to seeing here? What kind of song is this, they‘re not singing in English?

And the Monkees proceed to sing, a capella, a version of the song Riu Chiu. Nothing but their voices, no camera or editing gimmicks, no comedy, just the camera staying focused in one position as they sang. It wasn’t a pop song, it wasn’t a “holiday chestnut”, actually it was so far out of the realm of what a band like this would be expected to perform, that it had to be a jolt, it had to be not just a surprise but perhaps even a shock for some viewers.

And that is one reason of several I’m including it here on the Christmas list.

The song itself is a “Villancico”, a form of Latin American song and poetry which was performed and recited often during the Catholic mass, and was most popular from the 15th to 18th centuries. Specific meter and form was often the characteristic, and as they were recited during holiday church services, they would soon become most associated with Christmas.

The specific villancico “Riu Riu Chiu” had apparently become a Christmas tradition in certain areas of the US up to the 20th century and was often sung as part of a holiday choir or chorus program.

The abridged lyrics were as follows:

The refrain, or chorus which would begin the song as well as answer the verses:

Riu, riu, chiu la guarda ribera

Dios guarde el lobo de nuestra cordera

The first verse:

El lobo rabioso la quiso morder

Mas Dios poderoso la supo defender

Quizole hazer que no pudiesse pecar

Ni aun original esta uirgen no tuuiera

The second verse:

Este uiene a dar a los muertos uida

Y uiene a reparar de todas la cayla

Es la luz del dia aqueste mocuelo

Este es el cordero que San Juan dixera

The title phrase “riu riu chiu” represented a birdcall, some say by a nightingale and others say it was a kingfisher. The verses describe the Christmas story of the birth of Jesus and the Virgin Mary.

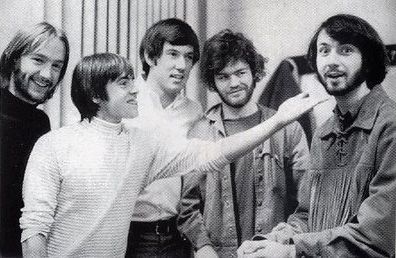

How did this song find its way to the Monkees? The story of how they fired Don Kirshner has been told so many times, it‘s part of rock legend and easily found in any number of sources for those interested. But the result of Kirshner’s dismissal was the hiring of Chip Douglas (who had most recently been a member of The Turtles and arranged ’Happy Together’) to replace him as the band’s producer. According to rock legend, again, Mike Nesmith found him in an LA club and point-blank offered Chip the job. Chip told Mike he had never produced a record, and Mike told him not to worry, he’d teach him everything he needed to know.

Chip Douglas with The Monkees at RCA Studios, 1967

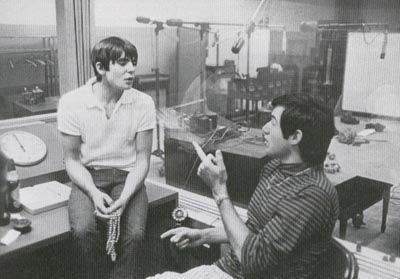

Davy Jones working out a vocal part with Chip Douglas, 1967

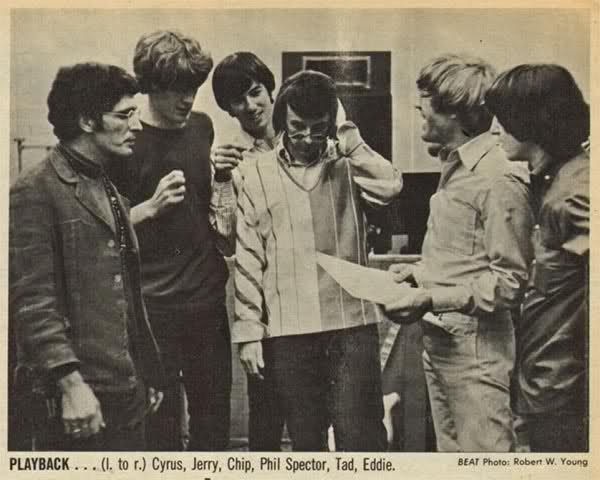

From KRLA Beat: Phil Spector with the Modern Folk Quartet and drummer "Fast" Eddie Hoh

On the Modern Folk Quartet’s second album, “Changes”, the group featured an abridged a capella arrangement of “Riu Riu Chiu”, singing only two verses and slightly extending the refrain.

Click above to hear The Modern Folk Quartet's "Riu Chiu" from 1964

In order to understand where this performance appeared in the whirlwind that was the Monkees’ year in 1967, one needs to consider what opinions and expectations were of this group. Their former music producer, Kirshner, had no respect for them as musicians and barely considered them individuals rather than part of his stable of artists, and saw them as disposable if not replaceable anonymous figures who would simply do as Kirshner said and all would be fine. This of course was not only false, but eventually backfired to the point Kirshner was shown the door after the band members went to the show’s producers (i.e. the real power) and demanded that they be given a chance to control and play their own music.

There was still an air of jealousy and resentment around the whole Monkees enterprise, a reputation which was blown out of proportion through various music journalists and commentators, and a reputation which led to five decades of flawed and sometimes false reporting on the history of the band and its legacy. There was supposedly resentment from their fellow musicians, yet each of them was known and performed in and around the LA music scene, and considered many of the so-called “hip” and relevant bands on the scene their friends. There was apparently resentment after Mike Nesmith had publicly revealed the methods Kirshner used to make their hits, which included all but banning the band members from most of the recording process and instead hiring session players to provide the backing tracks. This was standard practice, and the Monkees were not the first and certainly would not be the last to ever release records made under the exact same structure. Yet, they forever got tagged with the inaccurate line “they don‘t play their own instruments”, which segued into the even more inaccurate “they’re not real musicians”, much like I believe Kirshner viewed them prior to his firing.

1967 however did find the band with a handful of top 5 singles, a major hit TV show, two #1 albums on the charts and a third reaching top 5, successful tours including a successful British jaunt which found them spending time with The Beatles, two Emmy awards, and many other trappings of fame which made them among the most popular musicians and actors of the year, especially among the teenage audience.

Jimi Hendrix, Mike, and Peter on tour, July 1967

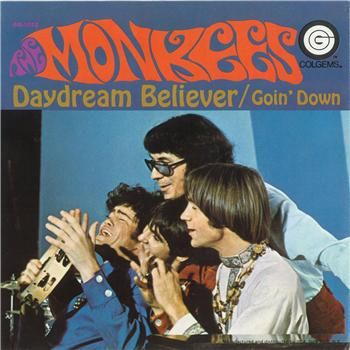

The number one single in the US for the entire month of December 1967

So what would the band do? Would they do a cover of a Christmas standard, but done in their current sound as heard on the album “Headquarters”, or their recent hit singles “Pleasant Valley Sunday” and “Daydream Believer“? Guitar-driven, electric country-folk-rock with splashes of keyboard and catchy vocals, most often from Micky Dolenz who had one of the best voices in pop music at the time?

None of the above, in fact nothing even close or remotely predictable was featured. The performance which aired that Christmas night in 1967 was as surprising as it is shocking as it is unexpected, and ultimately all of that context combined with the performance itself created a sublime and even stunning visual and aural television moment from a source you wouldn‘t have expected, whether in 1967 or the present day.

Yes, it’s basically the Modern Folk Quartet’s version as arranged by Chip Douglas, with subtle variation. But it also stands as a confident and self-assured statement, where the context again plays a part in the performance itself. The band performs this acapella, filmed live, with nothing to hide behind. They feature a relatively obscure piece of music, with a religious theme, sung in a language other than English, several hundred years old rather than a song with all the trappings of a modern pop song, as many bands and artists would have chosen in that same situation.

And that is another part of why it’s on the list. This performance was risky, and as they risked confusing if not alienating some of their fans who tuned in expecting traditional light holiday fare (or musical comedy) from their favorite group. Yet they took that risk, on their own terms, and delivered an unexpected classic.

Micky Dolenz had one of the most unique and accessible voices in 1960’s pop music. Not only could he sing, but he could sing with a certain emotion and connection to the listeners that marked the most successful pop artists. He was a consummate musician with that voice, and the hit records he sang with the Monkees still hold up as classics.

On the verses of “Riu Chiu”, Micky shines in a brilliantly understated way. He’s not showing off, but rather delivering the lyrics in a confident yet reverent style. Notice as he sings the verse, soloing on his own with no backing, which was a diversion from the MFQ’s version, Peter Tork looks over at him and smiles. Wherever that smile came from, it looks to an observer like a musician watching his fellow bandmate in full flight, loving every note and enjoying the moment.

I had not known the song prior to seeing this, and as a second-generation Monkees fan from the 1980’s who first saw them as MTV ran the episodes back-to-back, received the Arista greatest hits album as a Christmas gift, and would tape the songs off my TV as I watched them on Nickelodeon and WOR channel 9 from New York in syndicated reruns, at first I had no idea what the song was and wasn’t even sure about what I had just heard and seen. For one, the Christmas episode was not often shown during the syndicated reruns of the series. The song itself was only released when it appeared on a rarities compilation CD called “Missing Links vol. 2”. And the song had never been part of a Christmas music program or service I had seen. So it was new to my ears.

But I never forgot watching it on television, both the visual and the audio stuck with me. I’m guessing many viewers in 1967, the first generation audience, felt much the same way.

Note too that the “official” studio version of the song from Missing Links was not what was shown on television. The version on the compilations was a studio version recorded in August 1967 and featured Micky, Peter, Mike, and Chip Douglas but not Davy Jones. As performed on television, Chip was not featured and you get the four band members themselves, where you can clearly hear Davy’s middle voice in the live blend.

All of that meant if you didn’t have a copy of the Christmas episode from 1967, for years you did not have access to the performance. Such a radical, foreign concept in terms of 2013 to not have instant access to search and find something on demand, isn’t it?

Enjoy this short but compelling performance. If it’s new to your eyes and ears, maybe it will be a surprise or a shock. If you like it, love it, or think it’s below-average or worse, at least you have experienced it. And if you experience it now with some of the context which surrounded it in 1967, I hope it takes on a meaning and a significance not just as a musical performance but also as a statement coming from a band who was more often underestimated than they were given the credit as musicians which they probably deserved in retrospect.

And perhaps enjoying this performance will become a part of your own yearly Christmas and holiday music tradition as well.